Recently I published an article about the various performance characteristics of using regex in C#. Specifically, there are a handful of ways that we can use regular expressions in C# to do seemingly the same thing. I was curious about the differences, so I set out to collect some C# regular expression benchmarks… but I goofed.

In this article, I’ll explain my error so you can try to avoid this for yourself… and of course, I’ll provide new benchmarks and an update to the benchmarking code using BenchmarkDotNet.

What’s In This Article: C# Regular Expression Benchmarks

- The Invalid C# Regular Expression Benchmarks

- Being Lazy Like C# Iterators…

- The New Code for C# Regular Expression Benchmarks

- The New Results of C# Regular Expression Benchmarks

- But Wait! There's Caching!

- Wrapping Up C# Regular Expression Benchmarks

- Frequently Asked Questions: C# Regular Expression Benchmarks

Remember to check out these platforms:

The Invalid C# Regular Expression Benchmarks

In the previous article I wrote about C# regular expression benchmarks, I had results that illustrated enormous performance gains if you were incorrectly using some of the available C# regex methods. The benchmark results clearly indicated that the cost of creating a new regex object in C# was expensive, and even more expensive if you had the compile flag. So if you were doing this each time you wanted to match, you were paying an unfortunately high penalty.

You can watch the video walking through these benchmarks here to get a better idea, keeping in mind that the results we’re about to discuss are the correct ones:

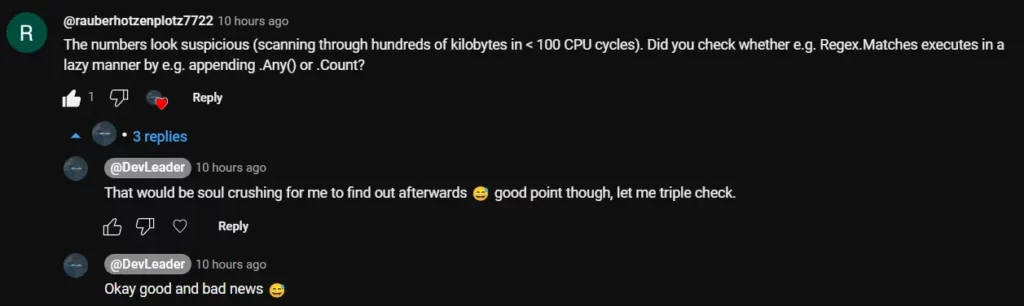

There was a great YouTube comment that came up pretty shortly after the video was released, and here’s what the viewer had to say:

That meant I had to go back to the drawing board to investigate!

Being Lazy Like C# Iterators…

As the viewer pointed out… it looks like MatchCollection that comes back from doing a regex match is lazily evaluated. That might be confusing if you haven’t heard of this concept before, but this is all much like using iterators in C#, which I have talked about extensively. If you want a bit of a crash course on the idea behind iterators in C#, you can check out this video for a walkthrough of my experiences:

Long story short: It looks like a line of code executes a method, but you’re simply just assigning a function pointer to a variable. The result is that instead of a method taking some amount of time to run, you instead have it execute nearly instantaneously.

But is the MatchCollection *actually* a C# iterator, or is it something else?

Revisiting The C# Regex Benchmark Code

Let’s consider the following code, which is one of the simple benchmarks from the previous article:

Regex regex = new(RegexPattern!, RegexOptions.Compiled);

return regex.Matches(_sourceText!);What we’re returning in that benchmark method is actually what’s called a MatchCollection. We could instead write that code as follows:

Regex regex = new(RegexPattern!, RegexOptions.Compiled);

MatchCollection matches = regex.Matches(_sourceText!);

return matches;The line in the middle of the code example directly above looks like it’s evaluating all of the matches, but indeed it returns nearly instantly. That’s definitely not what we wanted to measure! Instead, I was just measuring the cost of creating a MatchCollection instance vs creating an entire C# Regex object instance plus a MatchCollection instance. This explains why of course the two benchmarks that created instances were absolutely guaranteed to be slower — they did the same thing when it came to creating a MatchCollection instance, but they had their own associated overhead for regular expression creation.

What’s Happening With MatchCollection?

Well, it turns out that MatchCollection is not quite an iterator, but it certainly is lazily evaluated. If you keep jumping to the definition and go deeper into the code for MatchCollection, you’ll see the following:

private void EnsureInitialized()

{

if (!_done)

{

GetMatch(int.MaxValue);

}

}This is a method called in many spots within the MatchCollection class, and basically any time someone wants to access information about the matches, we eventually need to get into the GetMatch method. That method looks as follows:

private Match? GetMatch(int i)

{

Debug.Assert(i >= 0, "i cannot be negative.");

if (_matches.Count > i)

{

return _matches[i];

}

if (_done)

{

return null;

}

Match match;

do

{

match = _regex.RunSingleMatch(

RegexRunnerMode.FullMatchRequired,

_prevlen,

_input,

0,

_input.Length,

_startat)!;

if (!match.Success)

{

_done = true;

return null;

}

_matches.Add(match);

_prevlen = match.Length;

_startat = match._textpos;

} while (_matches.Count <= i);

return match;

}If you step through this code, you’ll notice that there’s state kept for how far along in the matches a caller is looking for. That means if this instance has not yet been evaluated that far along, it will then go attempt to evaluate that far based on the requested index. Looks pretty lazy to me! But if that wasn’t a giveaway… Look how the constructor doesn’t even take a collection of matches at the time of creation!

internal MatchCollection(Regex regex, string input, int startat)

{

if ((uint)startat > (uint)input.Length)

{

ThrowHelper.ThrowArgumentOutOfRangeException(

ExceptionArgument.startat,

ExceptionResource.BeginIndexNotNegative);

}

_regex = regex;

_input = input;

_startat = startat;

_prevlen = -1;

_matches = new List<Match>();

_done = false;

}Please keep in mind that this is what Visual Studio is showing me, and if you try checking the source at a later point it may be different in the dotnet code.

You can also follow along with this video here:

The New Code for C# Regular Expression Benchmarks

Let’s jump right into the new BenchmarkDotNet code for these regular expression scenarios, which will look VERY similar to before:

using BenchmarkDotNet.Attributes;

using BenchmarkDotNet.Running;

using System.Reflection;

using System.Text.RegularExpressions;

BenchmarkRunner.Run(

Assembly.GetExecutingAssembly(),

args: args);

[MemoryDiagnoser]

[MediumRunJob]

public partial class RegexBenchmarks

{

private const string RegexPattern = @"bw*(ing|ed)b";

private string? _sourceText;

private Regex? _regex;

private Regex? _regexCompiled;

private Regex? _generatedRegex;

private Regex? _generatedRegexCompiled;

[GeneratedRegex(RegexPattern, RegexOptions.None, "en-US")]

private static partial Regex GetGeneratedRegex();

[GeneratedRegex(RegexPattern, RegexOptions.Compiled, "en-US")]

private static partial Regex GetGeneratedRegexCompiled();

[Params("pg73346.txt")]

public string? SourceFileName { get; set; }

[GlobalSetup]

public void Setup()

{

_sourceText = File.ReadAllText(SourceFileName!);

_regex = new(RegexPattern);

_regexCompiled = new(RegexPattern, RegexOptions.Compiled);

_generatedRegex = GetGeneratedRegex();

_generatedRegexCompiled = GetGeneratedRegexCompiled();

}

[Benchmark(Baseline = true)]

public int Static()

{

return Regex.Matches(_sourceText!, RegexPattern!).Count;

}

[Benchmark]

public int New()

{

Regex regex = new(RegexPattern!);

return regex.Matches(_sourceText!).Count;

}

[Benchmark]

public int New_Compiled()

{

Regex regex = new(RegexPattern!, RegexOptions.Compiled);

return regex.Matches(_sourceText!).Count;

}

[Benchmark]

public int Cached()

{

return _regex!.Matches(_sourceText!).Count;

}

[Benchmark]

public int Cached_Compiled()

{

return _regexCompiled!.Matches(_sourceText!).Count;

}

[Benchmark]

public int Generated()

{

return GetGeneratedRegex().Matches(_sourceText!).Count;

}

[Benchmark]

public int Generated_Cached()

{

return _generatedRegex!.Matches(_sourceText!).Count;

}

[Benchmark]

public int Generated_Compiled()

{

return GetGeneratedRegexCompiled().Matches(_sourceText!).Count;

}

[Benchmark]

public int Generated_Cached_Compiled()

{

return _generatedRegexCompiled!.Matches(_sourceText!).Count;

}

}If you compare these benchmark methods to the previous article, you’ll notice they are very close with a very subtle difference: I’m returning an integer count instead of the MatchCollection. If you consider this and what I pointed out in the code earlier, Count is one of the properties on MatchCollection that will eventually try to evaluate the matches under the hood — as in, it will force the lazy behavior to get evaluated.

We can see that by factoring in this code snippet below:

/// <summary>

/// Returns the number of captures.

/// </summary>

public int Count

{

get

{

EnsureInitialized();

return _matches.Count;

}

}The New Results of C# Regular Expression Benchmarks

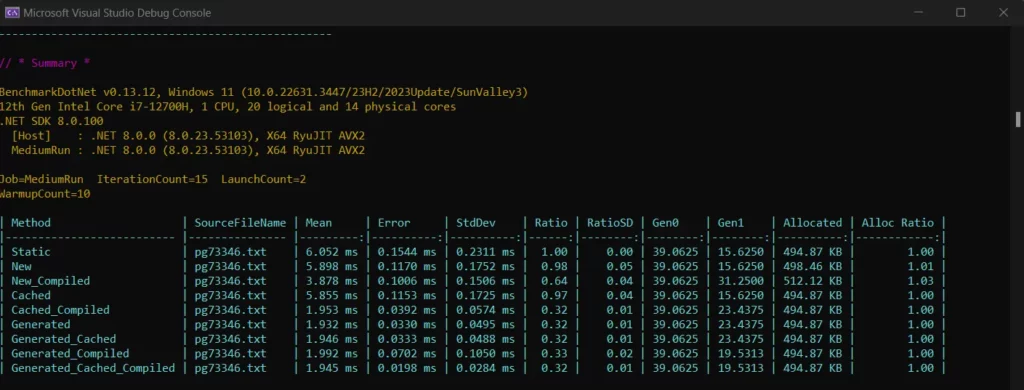

Now that I’ve come clean and admitted that I totally screwed up on my benchmarks AND provided you the updated code, let’s redo this analysis. Here are the newly run benchmarks:

Now here are some interesting things to make note of:

- The static method call is indeed the worst of all the options. While it’s nearly identical, creating a new regex is only a tiny bit faster as these benchmark results show. Under the hood, the static method call does try to get or add the regex to a cache, which seems to be a static collection of regular expressions that have been created. *MORE ON THIS SHORTLY*

- It looks like now in these benchmarks the overhead of compiling the regex is now WORTH doing, even if you’re going to do it each time you go to find matches. About a 56% performance boost! We need to keep in mind the pattern I’m using, the contents of data that’s being tested, and the overall length of that data as well.

- Simply caching the regex in a field shows very minimal performance benefits, if not just a rounding error, for this setup. Again, this could be largely due to the size of the data and the pattern being used, and perhaps a very short set of data to scan would make caching proportionally more advantageous.

- Now we get into the magic territory where we can see caching a compiled regex gives us performance that is 310% of the baseline. Not having to recompile is very helpful here!

- As predicted, like in the original article, all of the generated regexes are on par with each other, and in this test setup perform exactly on par with the compiled cached regex.

But Wait! There’s Caching!

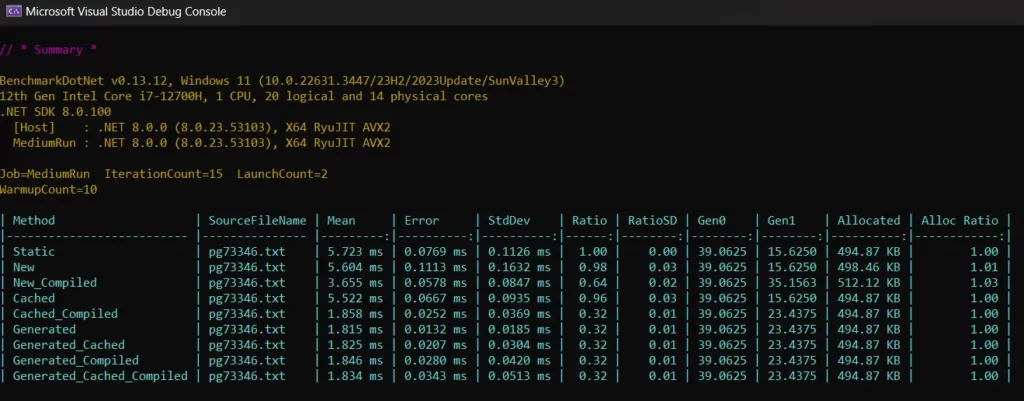

I wanted to be even more careful before publishing this follow-up article on C# regular expression benchmarks because of the first slip up I had. I recalled that the regex class has a RegexCache internal to the dotnet code that is running — and since we’re using the same pattern over and over… Are we caching things behind the scenes?

It turns out, we can change the cache size to zero by doing the following:

Regex.CacheSize = 0;If I add this line of code to the beginning of the benchmark runner, I can be assured that the caching is turned off. But just to be sure, I added this debug watch in Visual Studio after creating a regex just to sanity check:

typeof(RegexCache)

.GetField("s_cacheList", BindingFlags.Static | BindingFlags.NonPublic)

.GetValue(null)The result of this was seeing an empty cache, which is exactly what I was hoping for. A quick note is that RegexCache is internal, and I wasn’t sure the best way to get reflection to work in code to access this (i.e. not sure which assembly to go look at), but this does resolve properly in the debug watch list! But now you’re probably interested in the results:

Interestingly — there’s really no difference here. I suspect this is largely because the text we’re scanning through is large enough that the time it takes to evaluate regex matches mostly dwarfs the time it takes to create the regex objects. This is exactly what was *not* shown in the original article where the time to evaluate was basically zero because we never evaluated the matches.

Wrapping Up C# Regular Expression Benchmarks

Okay, now it’s time for some lessons learned…

- It’s okay to make mistakes. We’re all human.

- Mistakes are a great way to take ownership and show others that we can grow from messing up!

- Failing is one of the best ways to learn. I had absolutely no idea

MatchCollectionwas lazy after probably 10+ years of using Regex in C#.

At the end of the day, these new C# regular expression benchmarks are still very helpful in understanding just how big of an impact compiling your regex can have! Ideally, you don’t want to be recreating new regex instances, especially with the compile flag… but the performance of compiled regexes is awesome.

If you found this useful and you’re looking for more learning opportunities, consider subscribing to my free weekly software engineering newsletter and check out my free videos on YouTube! Meet other like-minded software engineers and join my Discord community!

Frequently Asked Questions: C# Regular Expression Benchmarks

TBD.